Lithography

From stone to chip

The annual AEPM conference was hosted by the Nederlands Steendrukmuseum (Dutch museum of lithography) in Valkenswaard (Netherlands) from 3-5 November 2016.

It was jointly organised with the IADM (Internationaler Arbeitskreis für Druck- und Mediengeschichte).

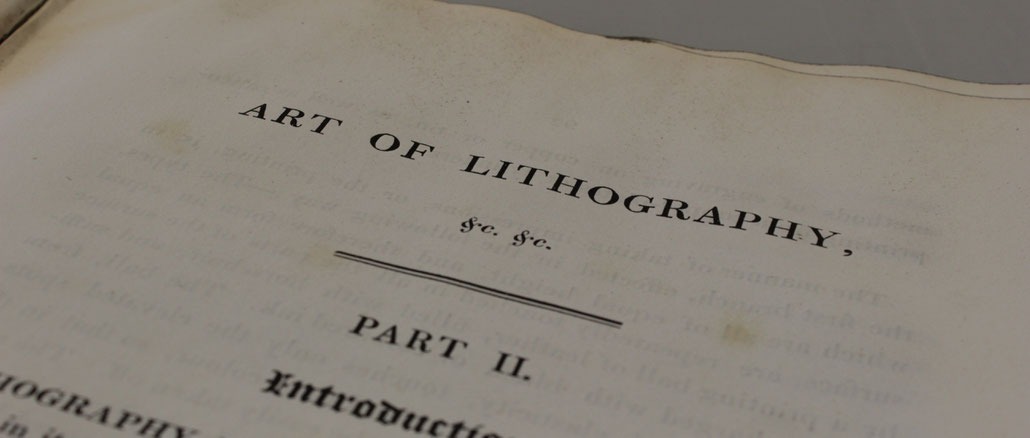

It is hoped that the conference will also provide an opportunity to bring together museums, people and ideas with a view to discussing the possibility of producing a travelling exhibition about lithography in 2018, on the anniversary of the publication of Aloys Senefelder’s manual of lithography.

Harry Neß (IADM / International Senefelder Foundation, Offenbach am Main, Germany)

Research topics in the relatively new field of media

archeology open new perspectives for the next chapter in printing and media history. In the first instance it is concerned with the identification and preservation of the materials,

equipment and tools of communication (hardware). It also deals with the analysis and long-term archiving of information available in digital form (software).

An example will be provided by the conservation of stocks of lithographic stones from the Hessian State Museum in Darmstadt with a discussion of the possibility of creating a “stone library” as a

national priority based on a chance find of litho stones from the Notendruckerei André during the construction of the S-Bahn in Offenbach (Germany).

The new forms of data transmission, both analogue and digital, which appeared in the 20th and 21st centuries raise questions about the use of sound recordings, computer collections,

diskettes, hard drives, pictures, magnetic disks, etc. Who were their producers, what technologies did they use, and who were the user groups? At the same time problems of obtaining changing

programs on computers, mobile phones and smartphones come into focus. Privacy, accurate data transfer and meeting the cost of maintaining databases and making tham accessible, receipt

of readability, digital rights management, etc., open new discussion concerning research and archiving, in which the IADM and the AEPM are involved. Because the electronically evolving

cultural artefacts of art, pictures, sound,s writing and language threaten to permanently disappear, their current reception is forgotten tomorrow.

Michael Twyman (Emeritus professor, Department of typography & graphic communication, University of Reading, United Kingdom)

The talk will focus on a collection of 56 lithographic stones, nearly all bearing work dating from the first half of the 1820s. The images on them relate to the archaeological discoveries of the Egyptologist William John Bankes, a friend of Byron, and heir to the family estate of Kingston Lacy (Dorset, UK), where the stones have languished for almost two centuries. Most of the stones show inscriptions that were drawn on stone in ink by George Scharf, a few others bear crayon drawings of archaeological monuments. The stones were prepared for printing, and in some cases printed for publication, by Charles Hullmandel, the leading British lithographer of the day. His imprint appears on most of the stones, in many cases with the date 27 November 1821. Most stones also bear the ownership marks of their printer (‘CH’ with a number), either painted on or carved into the underside of the stone. The reasons for this apparently unique practice will be discussed in the context of the early practice of hiring out stones, and particularly Hullmandel’s stated views on the matter.

Li

Portenlänger (Director

of the Eichstaett lithography workshop, Eichstätt, Germany)

Situated

in what is today Bavaria, the quarrying region Solnhofen has a worldwide reputation for the quality of the litho stones which it produces. Its limestone quarries were exploited as early as Roman

times and their stone was also used for the walls, floors and roofs of traditional farmhouses of this Jurassic region. A more sophisticated use of the yellow, grey and blue variants of this limestone

was made by architects of abbeys, churches, castles, and the baroque homes of burghers. Attempts to print from stones had been made before Alois Senefelder invented lithography, but

it was his ”chemical printing” that proved to be the veritable breakthrough in the field of planographic printing. The sucess of his printing process lead to massive quarrying of

stones as of the early 19th century and many abandoned quarries were reopened. Limestone from the Solnhofen area was characterized by its purity, its homogeneity and its density which

made it especially suitable for the production of large printing surfaces. In the course of the extraction of lithographic stone from the Solnhofen quarries many fossil-rich strata were

uncovered, providing abundant material for paleontological research. A new variety of fossil found in the region was even given the name “Archaeopteryx lithographica”.

Gunnel Hedberg (Malmö, Sweden)

The first lithographers (Fehr and Müller) – two Germans and one of their sons – were invited to Sweden by the crown prince Jean Baptiste Bernadotte at his own expense. They started printing in Stockholm in spring of 1818. Fehr was also one of the early printers in Denmark and he later started the first lithographic printing office in Norway. These two first printers were followed by a long line of printing offices in Stockholm. In the first decade there were about nineteen, mostly operating as an ancillary activity to other occupations. The activities of these first lithographic printers have been followed through official documentation (often concerning bankruptcies) , personal correspondence, advertisements in newspapers, and the imprints which the printers used. The picture which results is one of keen competition and the high personal price which nearly all of them paid as pioneers.

Jan af Burén (Museum of lithography (Litografiska Museet), Huddinge, Sweden)

Lithography was introduced in Sweden in 1818 by two German lithographers and printers at the request of the Swedish king, the former French Marshall Jean Bernadotte. Soon a good working knowledge of lithography was acquired but it was not until the beginning of the 1840s that chromolithography was introduced in Sweden. The introduction of this technique followed relied on the skills of immigrant German lithographers and imported handbooks, the most important of which was Heinrich Eduard Pescheck and Leo Bergmann’s Das Ganze des Steindrucks. Another source was Robert Bertram’s New Lithochromie, which was translated into Swedish in 1840. The same year Johann Friedrich Meyer from Berlin and Hamburg established J. F. Meyer & Co Lithographic Institute. In 1848 Meyer returned to Berlin to learn the latest techniques in chromolithography. In 1844 the Swedish lithographer Axel Jakob Salmson established a lithographic printing shop. His first chromolithographies were printed with the help of handbooks. In 1840 Robert Bertram’s book on lithochromie – a form of reproduction using oil colours – was translated into Swedish. A few years later the second edition of Peschek’s Das Ganze des Steindrucks was released. Here again the word lithochromie was used, but now meaning chromolithography. Both Meyer and Salmson followed the techniques described in the book, which combined working with several colour stones and hand coloured details. Later, at the beginning of the 1860s, Meyer and Salmson printed true chromolithographies. From then on the technique of chromolithography spread to all important lithographic workshops in Sweden.

Johan

de Zoete (Haarlem,

The Netherlands)

Directly after the invention of photography experimenters tried to apply the principles of this new technique to printing. The earliest experiments were made in intaglio. The daguerreotype consisted of a photographic image on a silvered copperplate, and copper was a material printers were familiar with. Around 1855 the Frenchman Alphonse Poitevin developed a process of photolithography that gave acceptable results. The method wasn’t very practical though. The biggest problem was the rendering of the continuous tones of the original. Other methods were effective as long as the original consisted of pure black and white. This didn’t give spectacular results and was confined to artwork like drawings, not photographs of the ‘real world’. A method like that of Colonel Henry James Scott in Southampton, ‘photozincography’, was however used with some success in the production of facsimiles of old texts. Another process was based on an invention by Eduard Isaac Asser, an Amsterdam-based amateur photographer. His method was adopted by several printing firms, even though it also failed in the true rendering of continuous tones. A later development was Charles Eckstein’s ‘Steenheliogravure’, which was used to make some stunning pictures. With the invention of halftone photography using a screen, around 1881, the technique of representing continuous tones by dots of various sizes was successfully applied to lithographic printing.

Gerhard

Kilger (International

Senefelder Foundation, Offenbach, Germany.)

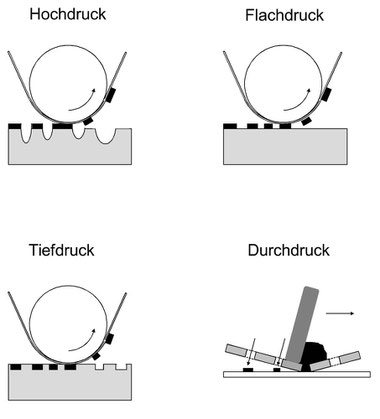

Alois Senefelder’s lithography was from the beginning

not only an important printing technology for reproduction of works of art. It was also used as an artistic medium by many artists. Lithographs were usually prepared and printed by

experts.

Since Senefelder’s time, however, artistic lithography undergone considerable development in the post-industrial period. Similarly, the professional expertise has disappeared along with

the necessary materials for this demanding printing process. Experiments and creative new approaches developed by artists have, on the other hand, created completely different and new

possibilities with lithography. Rarely has an industrial technique experienced such a change in the hands of artists after its decline.

Gerhard Kilger will illustrate these changes with examples taken from among the winners of the International Senefelder Award.

Jean

Drache (Germany.,

educational workshop for lithography)

Since its invention, lithography has lost none of

its attraction for artists. Although it has been largely replaced by offset printing for commercial work, artistic printing from stone is still very much alive.

Offset printing also provides niches that are of interest to artists. While lithography is mainly used by practitioners of painting and drawing, hand offset printing is if particular interest for

photographers and media artists. The similarities and specificities of both techniques will be discussed in the presentation which will also provide an insight into the work of a hand

offset workshop and a lithography workshop at the Academy of visual arts in Leipzig.

Bruno Bruni - Lithographie

Roger

Münch (Director,

German Newspaper

Museum,

Wadgassen, Germany)

Although history has shown very clearly the epochal significance which the various lithographic techniques have for the printing industry, the name of the inventor of the lithographic process, Alois Senefelder, is still little known among the general public. Why is this the case? This question was the starting point of the idea to produce a travelling exhibition on the subject. For many years now – decades even – both the Nederlands Steendrukmuseum and the International Senefelder Foundation (ISS) have been trying to remedy this deficit. As board members of ISS Peter-Louis Vrijdag and Roger Münch began to develop and to promote the idea of a Europe-wide special exhibition. Inspired by Oscar Wilde’s famous play, “The importance of being Alois” is aimed at raising interest in this exciting inventor personality of the modern age, showing how the principle of lithography continues to affect the modern communication technology.